Pancho and Lefty: An Appreciation

By Nelson Smith

August 7, 2020 - 21:33

|

“It is one of the characteristics of human nature to worship at the shrine of anyone who excels in any line, let it be for good or for evil.” (Wayman Hogue, 1932)

I’m not altogether sure what it was that compelled me to revisit a song generally considered to be one of the greatest country songs ever written, and possibly the finest of the many great “story” songs that have, over the years, come out of the State of Texas. Maybe it’s the attention paid, over the last three years, to the U.S.-Mexico border and, by default, the State of Texas, which contains a good half of that border via the Rio Grande. Maybe it’s the undeniable lawlessness that seems to have infected much of Mexico, a lawlessness born of drugs and desperation that the American president shamelessly exploits. Or maybe it’s the fact that the song was mentioned admiringly in Ken Burns’s superb documentary, “Country Music”. I really don’t know. But, for some reason it seemed time.

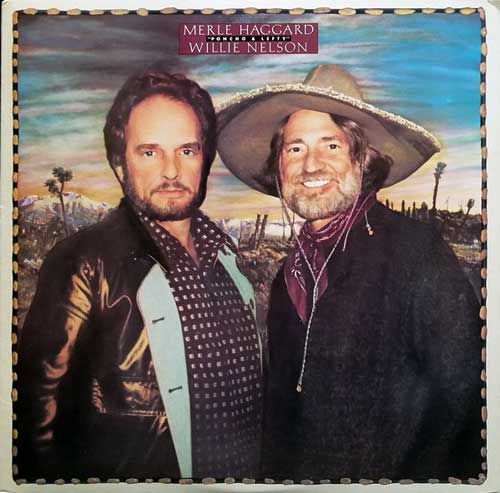

The song that I’m referring to is Pancho and Lefty. Written by Townes van Zandt, it achieved its most perfect form in the shimmeringly, achingly, almost startlingly beautiful version by Emmylou Harris (on her 1976 “Luxury Liner” album, with vocal harmonies provided by the redoubtable Rodney Crowell) and was made famous by Willie Nelson and Merle Haggard on their 1983 album, titled Pancho and Lefty. Any number of artists have covered the song, including the great Steve Earle. Western Writers of America members ranked Pancho and Lefty #17 on their Top 100 Western Songs list. No doubt, it’s a great song. But, beyond that, there’s something special about it that, in my view, sets it apart from the others.

First, it’s worth clearing up any possible myth-understandings as to the origins of the song. Townes van Zandt claimed that the song came to him almost as if in a dream. “I realize that I wrote it, but it’s hard to take credit for the writing because it came from out of the blue. It came through me, and it’s a real nice song, and I think, I’ve finally found out what it’s about. I’ve always wondered what it’s about.” That was Townes van Zandt talking to an interviewer. He denied that there was any connection between the character Pancho and the famous Mexican bandit Pancho Villa, although there are enough similarities (including an alleged trail-buddy of Pancho Villa whose name could be construed to have meant something like “Lefty” in Spanish) to make the case for such a connection. In my view, a connection is unlikely, it doesn’t really matter and is not worth drilling into. Townes van Zandt could be abstruse - consider his lyric tendencies in songs such as If You Needed Me - and droll, not at all above a pile of leg-pulling. He was very much sui generis, and so is Pancho and Lefty.

Structurally, the song is divided into four stanzas, separated by a common refrain. The first two stanzas are sung before the first refrain, and the third and fourth stanzas are each followed by the refrain, which is repeated, slightly but significantly altered, at the end of the song. In the first stanza, we encounter a narrator who is speaking directly to another character. It has been posited by some that that character is Lefty, but by others that it is Pancho. For my money, although I have my suspicions, it isn’t at all clear, and indeed it may be neither. Nor is it clear that all the stanzas are even connected, and that uncertainty, that ambiguity, is part of what makes this song so wonderfully enigmatic:

Living on the road my friend was gonna keep you free and clean

Now you wear your skin like iron and your breath's as hard as kerosene

You weren't your mama's only boy but her favorite one it seems

She began to cry when you said goodbye and sank into your dreams

The narrator speaks directly to the character, and it is clear that they have some sort of relationship. They are friends, or so the narrator claims. It behooves us remember that there are people who annoyingly, indeed creepily, refer to a person whom they hardly know as “my friend”, and whose character, as evidenced by such false familiarity, could well be questionable. So, the narrator, whose motivation for embarking on this poetic voyage is unclear, may be entirely unreliable. I think van Zandt would not have been unhappy to hear that.

But the overwhelming body of evidence suggests a real relationship, perhaps an older person of the character’s mother’s acquaintance, who knew that he wasn’t her only boy but her favorite one (it seems – the narrator is unable to be more certain, and we are not told how he – or she – has arrived at this conclusion). The narrator also knows that she cried when he said goodbye, which should not be surprising, but then this may just be a lyrical set-up for a rather dramatic change of tone: “and sank into your dreams”. This is not a dream arc in the normal sense and indeed suggests something more nightmarish than dreamy. It is also the first of several jarring tone-shifts.

The first question that the listener must face is this: who is the narrator and to whom is he/she talking in such a familiar way? It could be Pancho and it could be Lefty. Whoever it is, he came from a large family (“You weren't your mama's only boy but her favorite one it seems”), which tilts it in Pancho’s favour, if you believe that Pancho’s parents were Catholic (highly likely, considering where he seems to have come from, Mexico). But the song also plays with space and time. Is the narrator talking to a person in the here and now? If so, then it is to Lefty that he/she speaks, since Pancho died some time ago, as we learn in the next stanza. But then, one might ask, what is the “here and now” anyway? It is entirely possible that the narrator is looking wistfully at an old sepia-tone daguerreotype of Pancho. Quite simply, we will never know, just as we will never know anything about the narrator – age, sex, race, relationship with either Pancho or Lefty – except that he/she has a story that he/she wants to get off his/her chest and knows the players, at least one of them, fairly intimately.

The obvious follow-up question is, why was living on the road going to keep the character free and clean? What did he have to get away from? And how and why did it fail? How did he end up wearing his “skin like iron” and having “breath as hard as kerosene”? We’re barely into the song when we encounter these two rather startling similes. Utterly poetic in their improbability, they serve the purpose, along with the black-is-white notion of sinking into one’s dreams, of creating a vague through-the-looking-glass atmosphere that is sustained throughout. But they shed no light on who the narrator’s co-locutor is. It could be either Pancho or Lefty. Or it could be neither.

Almost as though there were no connection to the first stanza (and there may well be none), the song careens ahead into stanza #2. We now encounter Pancho, through the narration of someone (possibly not the same as for the first stanza, but what would the point of that be?) who, in an abrupt change of perspective, now turns to his/her audience, a group of men that the narrator seems to know and addresses familiarly as “boys”, saying that:

Pancho was a bandit, boys, his horse was fast as polished steel

He wore his gun outside his pants for all the honest world to feel

Pancho met his match you know on the deserts down in Mexico

Nobody heard his dyin' words - ah but that's the way it goes

We learn all we really know about Pancho in the first two lines of the stanza. It is a fractured descriptive, to say the least. The images are, as in the first stanza, striking and absurd and unsettling, but there might be a sort of logic to it all, rather as in the looking-glass world that Alice walked into. For example, a gun is made of polished steel, and it has been said that a particularly good horse, like Superman, the man of steel, can run faster than a speeding bullet. As I said, a sort of logic. And what bandit doesn’t wear his gun outside his pants? It would be weird to wear a gun inside one’s pants – unless it isn’t really a gun that we’re talking about. But we ask too much of our literary devices at our peril. And I digress.

But here’s the thing: Pancho was a “bandit, boys”, a statement which, in its breezy declaration, suggests a certain enthusiasm for the outlaw. Yes, a bandit for sure, but by the way he wears his gun, Pancho is in some way looking out for “all the honest world”, that is, those who are not bandits, do not carry guns, and go about their business peaceably and honestly. In wearing his gun outside his pants, he is giving fair notice to the honest world, and even if they are unable or unwilling to see it, they can surely feel it, probably from miles away. One can only suspect that they revere him, even as they fear him. Those first two lines tell you that he is something special, not a member of the “honest world” but perhaps honourable in their eyes, notwithstanding. That would put Pancho within the frame of a time-honoured tradition, going back at least to the days of Robin Hood – the outlaw hero.

Nowhere is the outlaw more revered than in America. But why? Why do wild-west outlaws like Jesse James and Pancho have such a fan-base, given how awful so many of these outlaws were. In America, the home of the brave and the land of the free, it goes deep. The American outlaw-hero is the embodiment of the frontier impulse, the desire, possibly even need, to live at the fringes of, or even outside, the established order. This is a person who chooses liberty over orderliness, and is prepared to accept the riskiness and disorder of the outlaw life in order to achieve that liberty. He has likely been driven to it by what, in his view, is an oppressive system that threatens his liberty, and, whatever his character flaws, he is endowed with a personal trait that Americans, more than any other people, admire. That is, the compulsion to live free. As in, “Give me Freedom or give me Death”. This ethos, by the way, is still very much alive and well in many parts of America.

The idea of a rugged individual who breaks norms and challenges the status quo, maybe even changes the course of history, is powerfully seductive. For one thing, this individual dares to do what we ordinary people couldn’t imagine doing ourselves. It also validates our sense that we are all in this together, not as a collective (how un-American!) but as a group of identically valuable and motivated individuals. A bunch of Davids tilting against the Goliath of the state, the man, the elites, those who, possibly out of corrupt motive, would take away our freedoms. If that outlaw also gives some of the proceeds of his criminal acts to the poor and needy, he may well be sainted. By the way, it is interesting to note that the name “Pancho”, while mostly used as a nickname for people named "Francisco" and also taken to mean "fuss", "tantrum", or "problems", most importantly also means “freedom”.

A corollary to this outlaw-as-hero phenomenon is the revulsion often felt towards those who bring down the outlaw-heroes. Perhaps the best example of this is Jesse James’s assassin, a person who rode with him and who was his friend, a man named Robert Ford. Despite the fact that, in killing James, Ford probably saved countless other lives, he is commonly reviled as a low-down killer of a superior being and, much worse, a man who betrayed his friend. In his “Inferno”, the poet Dante describes in agonizing detail a hell that is comprised of nine concentric circles, each moving ever lower, to the centre of the earth, where Satan is held in bondage. The sinners in each circle are punished in a manner befitting the crime that the circle represents. It is no surprise that the lowest circle, the ninth circle, is reserved for those who betray family, friends and community.

All the Federales say they could've had him any day

They only let him slip away - out of kindness I suppose

The refrain is, at the very least, an admission that the Federales – the Mexican state police – are, or were, incompetent. It is a shame-faced admission in the form of a denial. They clearly were not able to capture Pancho and came up with the excuse that, although they “could've had him any day”, they allowed him to slip away – presumably more than once. Why? The narrator’s take on this drips with a sort of droll cynicism. “Out of kindness, I suppose.” Yeah, right. They’re a bunch of Keystone Kops who couldn’t catch a cold, let alone the formidable Pancho. This amounts to a touch of comic relief, provided by a world-weary someone who sees it for what it is. But there are a couple of things to note here. First, it seems that the Federales were not the “match” that Pancho met “on the deserts down in Mexico”. They may have been necessary to Pancho’s downfall, but clearly not sufficient. Presumably, they needed help. Second, unlike the second verse, the tense is now the present. As I have said, Van Zandt plays with time and space throughout. The narrator is now speaking from a time when Pancho’s demise is fairly recent. All the Federales say, as in, right now. A present from somewhere in the past. It feels as if the narrator is trying to get to the bottom of it, and the Federales are covering some tracks. We only let him slip away, but could have had him any day, and when that day arrived, we laid him low, no doubts or hesitation.

Lefty he can't sing the blues all night long like he used to

The dust that Pancho bit down south ended up in Lefty's mouth

The day they laid poor Pancho low Lefty split for Ohio

Where he got the bread to go there ain't nobody knows.

Finally, we are introduced to Lefty, with a picture of him trying to sing and finding himself no longer able. Whether he ever sang the blues all night long is not terribly relevant, and in fact may well be yet another example of Townes van Zandt’s tendency to surprising, even distracting, literary devices. In this case, the real importance of the first line lies in its ability to deliver the second, one of the more clever and elegant metaphor-images in all of country music and an important link to the second stanza. In stating that “the dust that Pancho bit down south ended up in Lefty's mouth”, while not directly implicating Lefty in the death of Pancho, the narrator has made it clear that Pancho’s death came to have a significant impact on Lefty’s quality of life. Moreover, there is a direct, almost physical connection between Pancho’s death and Lefty’s state of well-being. Through time and space, that dust ended up in Lefty’s mouth. How it got there is anyone’s guess, and one might well fear to speculate.

On a similar note, we learn that, even as Pancho is being buried (“poor” Pancho clearly held favour with the narrator), Lefty splits for Ohio, presumably, although by no means certainly, his home town, and “where he got the bread to go there ain't nobody knows”. As in, somebody actually does know, the narrator says, and, in fact, I know. And so do you. Certainly, the Federales know.

The poets tell how Pancho fell and Lefty's living in a cheap hotel

The desert's quiet and Cleveland's cold and so the story ends we're told

Pancho needs your prayers it's true but save a few for Lefty too

He only did what he had to do and now he's growing old

This last stanza may well be one of the greatest in all of country music. It just says so much. It speaks of the glorification of the bandit that is so characteristic of the legend-lore of the American west, and of the loss that his death inflicted on his world (“the desert’s quiet”). That his world was a desert, with all its deprivation and harshness and lawlessness and void, tells you much about Pancho. But the stanza also speaks of the desolation of the one-time trail-buddy who, it seems reasonable to believe, betrayed his friend and now lives in a cheap hotel in a cold northern city. Interestingly, the hell described by Dante, by the time he arrived at the ninth circle, was not all fire and brimstone. Rather, it was a vast frozen lake called Cocytus, in which sinners were embedded, usually up to their necks. If revenge is best served cold, then perhaps so is atonement.

While the name Pancho means freedom, if also disruption, the name Lefty is derived from a Latin word that has rather negative connotations: sinister. So, it would be easy to present a Manichean picture of a good (free) guy, albeit that he is a bandit, brought down by a bad (sinister) guy who had only base personal motives for his betrayal. But it’s just not that easy, as the final stanza makes clear, and, in the end, this is what makes Pancho and Lefty such an ineffably great song: the ambivalence, the moral opacity, the many shades of gray where we prefer our blacks and our whites. It’s Chinatown, Jake.

Neither man is/was an angel, far from it. Both need our prayers, Pancho, it’s true, but Lefty too. Save a few for him. After all, he only did what he had to do. Didn’t he? It wasn’t an easy decision for Lefty, to betray a friend. But the money would really help, and there is a bounty on offer, for one very bad bandit. Besides, a lot of lives will be saved by bringing Pancho down. You have to wonder how long it took for Lefty to make his decision.

Pancho probably went straight to hell after he died. But Lefty’s been living in his own cramped quadrant of hell for so many long years, in cheap hotels and bad dreams, that he’d feel right at home, down there with Pancho.

And now he’s growing old. Nothing more needs to be said here. The poignancy and pathos are almost oppressive.

And the Federales have now grown old too. In the repeat of the refrain, they are just a few in number and gray, but still maintain that they could have had him any day, we only let him go so long, we just let him hang around. All those years ago. Van Zandt plays with space and time right to the end, which only adds to the melancholic, elegiac feeling of this wonderfully mysterious song. They are all suddenly in the here and now, not standing at Pancho’s gravesite muttering about what could have been and slipping an envelope into Lefty’s hand, probably his left hand. They may even be there, in that hotel room with Lefty, as they probably have been, as Pancho probably has been, every day, sober or not, for so many years that Lefty has stopped counting.

And we’re there too, courtesy of our narrator. In the room or hovering outside, peering through the window. Who was the narrator? Was there more than one? Was it a man or a woman? What was his/her relationship to either Pancho or Lefty? It’s hard to say.

Ah, but that’s the way it goes.

Related Articles:

Song of the Lion book review

2016 J-Pop Summit Announces Song and Dance Contests

Touch You There: The world of the Song Maker

A Devil and Her Love Song: Volume 13 Advanced manga review

A Devil and Her Love Song: Volume 12 manga review

A Devil and Her Love Song: Volume 11

A Devil and Her Love Song: Volume 10 manga review

A Devil and Her Love Song: Volume 9 manga review

A Devil and Her Love Song: Volume 8 manga review

A Devil and Her Love Song: Volume 6 manga review