DC Comics - A History, Part 2

By Philip Schweier

March 29, 2007 - 06:01

Crisis

In the years immediately following the defeat of the Axis, readership continued to decline. Many of those who had read comics in their youth had been sent away to serve their country. Many, sadly, failed to return. Those that did had outgrown comic books. Four-color adventures were small potatoes compared to what they’d been through. The kids who’d read comics a decade before were now grown, and only interested in settling down to simple civilian life. Wives and girlfriends were eager to start families and enjoy the prosperity that post-war life promised. Unfortunately, it wasn’t a promise kept.

Having licked the Nazis and the Japanese, America sought out a new enemy, finding it in the form of communism. The United States entered the Korean Conflict in the early 1950s, with no significant results other than maintaining the status quo. Meanwhile at home, Sen. Joseph McCarthy led the communist witch-hunt in congress, and Hollywood figures were brought to Washington to testify before the House Un-American Committee. Those that refused to meet the demands of HUAC were black-listed.

Unsatisfied, America continued to seek a scapegoat for all the disappointments and broken promises of the past few years. It wouldn’t be long before psychiatrist Dr. Frederic Wertham provided one.

|

| Dr. Frederick Wertham, author of Seduction of the Innocent. |

Wertham also made claims that Batman and Robin were homosexuals, Wonder Woman a lesbian, and the Superman/Lois Lane/Clark Kent triangle formed a menage a trois of staggering perversions.

Despite Wertham’s dubious research, it panicked parents and prompted congress to convene hearings examining the effects of comics on American youth. In typical governmental fashion, the comics industry came out on the short end of the stick. Questions arose regarding the suitability of some of the material for young readers, for comics had always been perceived to be a children’s medium.

In the end, the industry chose to police itself, rather than allow the government to do it. Publishers united to establish the Comics Code Authority, a governing board to set down guidelines for what may be suitable or in good taste for their perceived audience.

Through these hard times, National looked for new material to build upon, foregoing horror and crime titles in favor of more innocent funny animal books and humor titles starring the likes of Bob Hope and Jerry Lewis. The publisher also explored new genres such as Westerns, science fiction and romance. Many of its super-hero titles faded into obscurity. Only the strongest of characters, such as Superman and Batman, managed to maintain viable sales figures.

By the early 1950s, DC had assumed complete control over the growing Superman empire of publishing and merchandise. Originators Siegel and Shuster had sold their creation to the company for a pittance, and by some accounts were slowly eased out the door, costing the two men a fortune in profits in the process. Editor Mort Weisinger was now the creative force behind the Man of Steel, and writer Jerry Siegel was simply one of the many freelance writers available to him. Joe Shuster, his eyesight failing, had long ago turned the art chores over to others.

Part of National’s success was the ability to parlay its characters into other mediums. Both Batman and Superman were featured in a handful of Saturday matinee cliffhangers, and led to the production of the syndicated Adventures of Superman starring George Reeves.

|

| George Reeves and Phyllis Coats as Superman and Lois Lane. |

The publisher maintained strict control over the show. Contracts with the performers were decidedly in the producers’ favor. Beginning with the third season, production was cut from 26 episodes a season to 13, loosening the budget enough to permit the series to be filmed in color. Unfortunately, the actors’ contracts had specified 52 episodes; believing they were signing for an additional two years, they found themselves committed for four.

The Silver Age

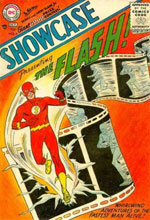

Meanwhile, back in New York, efforts were made to capitalize on the television success of Superman by rebuilding the comic book line. In 1955, under the direction of Harry Donenfeld’s son Irwin, the editorial staff decided rather than launch a series of potential failures, National would establish Showcase, an anthology title designed to feature multiple creations. Those that proved to be successful would graduate to their own book.

|

| Long-time DC editor Julius Schwartz, during the Silver Age of comics. |

He began by eliminating everything that had been established, intending to create an entirely new character, keeping only the name. “I worked in the same office with a fellow editor named Robert Kanigher. So I sat down with him and immediately thought of the story. How can we try something different, try and make it more realistic? For example: How did the so-called Golden Age Flash get his powers? He was working in the laboratory and dropped a vial of heavy water, of which there is no such thing. And he inhaled the fumes of heavy water and became fast. I said, ‘There's got to be a more logical explanation. How about if a scientist is working in a laboratory and a bolt of lightning comes in and hits the chemicals and they splash all over him?’ Well, a bolt of lightning travels 186,000 miles a second. That's a more reasonable explanation.

|

| Showcase #4 featured the debut of the new Flash. |

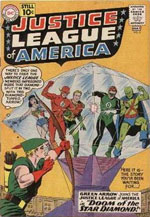

According to Schwartz, sales were so high, he was asked what to revive next? “I said, ‘Green Lantern.’ We put out Green Lantern. Unbelievable sales. Then they said, ‘What do you want to do next?’ and I said, ‘Justice Society of America, with all the new heroes put together.’ But I thought, ‘No, I don't like the name. Society, that's a social club.’ Let's call it Justice League of America.”

Harry Donenfeld and Martin Goodman, the publisher of Marvel Comics, played golf from time to time, and it is reputed that Donenfeld’s boasting prompted Goodman to mandate the creation of the Fantastic Four, breathing new life into that company, and locking the two comics publishers in perpetual conflict. While fan-bases have varying degrees of fervor, Marvel’s longtime editor-in-chief and publisher emeritus Stan Lee has often referred to his crosstown rival as the “Distinguished Competition,” and many writers, artists and editors have jumped back and forth over the years.

Strange Adventures

|

As Marvel’s competition heated up, National countered with a number of potentially off-beat ideas, such as Metamorpho the Element Man, the Inferior Five, the Secret Six, the Creeper and Deadman, as well as anthology titles such as Mystery in Space. New markets beyond comics began to open up, as Superman starred both on Broadway and Saturday morning cartoons, and Batmania swept the nation.

In his earliest days, the Caped Crusader was a mysterious creature of the night, but the advent of Robin the Boy Wonder lightened the mood of the character, turning him into a costumed cop. The comic relief of Alfred the butler furthered this effort, but by the mid-1950s, Mort Weisinger became involved, sending the character in directions that longtime fans have come to regard as a dark time for the Dark Knight. Adventures took Batman and Robin back in time, into the future, to alien worlds and saddled him with a supporting cast that was nothing less than carbon copies of Superman characters

By the mid-60s, Batman sales were lagging, and in danger of being cancelled. Once again, Julius Schwartz saved the day. “When I took over Batman, I decided to do something very drastic,” he said in Atlanta. “I decided to kill of Alfred the butler... and I brought in Aunt Harriet, the aunt of Dick Grayson.”

However Bill Dozier, a producer at 20th Century Fox, was interested in optioning the character for television. One story has it that an ABC network exec was at a party at the Playboy mansion and observed Hugh Hefner and guests getting a hoot out of the goofy low-budget serials of the 1940s, and saw potential in the property. Pop culture had become fodder in a lot of mediums, and the network had a narrow window of opportunity before the bloom was off the rose. That made it foolproof. If the show succeeded, the wave could continue a bit longer. If not, failure could be laid at the door of the fickle public, not bad programming.

“So the first script came in,” continued Schwartz, “And there was no Alfred the butler in this. He (Dozier) said, ‘Where's Alfred the butler?’ and he was told they killed him off. Suddenly they're saying they want him back again. So I had to figure out a way to bring him back, and I did it. And so Alfred the butler was restored, and so both Alfred and Aunt Harriet appeared in the television series.”

Despite a poor response with test audiences, the network spared little expense in promoting the show. It premiered on January 12, 1966, and was an instant hit; popular with kids for the super-hero action, popular with adults for the campy humor.

|

| Adam West and Burt Ward Starred as Batman and Robin. |

Not only was the show a hit with audiences, but also in Hollywood. Regular cast villains included Cesar Romero, Frank Gorshin, and Burgess Meredith, who had the time of his life portraying the Felon of Fowl Play, the Penguin. Writers kept a script on hand for him whenever he was available. For many actors, it became Hollywood’s most popular gig, leading writers to create an entire new rogues gallery for Batman to battle. Performers such as Vincent Price, Shelley Winters, Milton Berle, Tallulah Bankhead, and Liberace all made appearances.

Batmania infected show business like never before. Jules Feiffer, in his book The Great Comic Book Heroes writes, “Comic books, first of all, are junk. To accuse them of being what they are is to make no accusation at all; there is no such thing as uncorrupt junk or moral junk or educational junk.” If one applies Feiffer’s reasoning to television, there is no such thing as good junk, only successful or unsuccessful junk. Batman made the leap from one junk medium into another. With one feeding off the other, each became a success.

Lorenzo Semple Jr., chief writer and editorial adviser for the show, set the tone of the show. Horribly corny became high camp, silliness became satire, and insipid pablum became ingenious programming. To some, Batman was so bad, it was good. A feature film followed the first season, offering producers a larger canvass. Included in the movie were new toys, the bat-boat and bat-copter.

But by the end of the second season, the numbers began to slip. The joke had worn thin, so producers did what they could to inject the show with new life. One solution in the third season was to introduce female character. “That was my assignment,” said Julie Schwartz. “So I came up with the idea of Batgirl.”

The show followed the idea as it was laid out in the comics, with the curvaceous Yvonne Craig portraying Commissioner Gordon’s crime fighting daughter Barbara. But even a little sex appeal wasn’t enough to hold viewers.

Following ABC’s cancellation, NBC expressed an interest. But overzealous workmen had already destroyed the sets, and NBC wasn’t up for the task of rebuilding. After 120 episodes, the series was dead.

The impact of the 1960s television series reached well into the corners of pop culture. In the years that followed there was rarely a news story written about super-heroes or comics which did not feature the sound effects from the old show. Headlines often contained “POW! ZAP!” before going on to detail the evolution of costumed crime fighters, or that comic books had become big business.

In fact, business was so good that the company was acquired by Kinney National Services in 1967, which later also bought Warner Brothers film studio, paving the way for the eventual Time-Warner empire. Artist Carmine Infantino rose in ranks, first to art director, then to editorial director. Eventually he would rise to publisher.

Tomorrow: Comics come into their own

Related Articles:

DC/Vertigo Notices "Black History Month" with Incognegro

DC Comics - A History, Part 3

DC Comics - A History, Part 2

DC Comics - A History, Part 1