Comics /

Cult Favorite

Comics for 45-Year-olds

By

Philip Schweier

August 17, 2013 - 19:51

|

| Paul Pope |

One of the stories that came out of last month’s

Comic-Con has been getting a lot of air-play in the Inter-webs. It was related

by Paul Pope and first published by Robot 6 at, shall we say, “another Web

site.”

Pope had enjoyed some healthy success working on Batman, which led to a

conversation with someone whom Pope identifies only as “the head of DC Comics.”

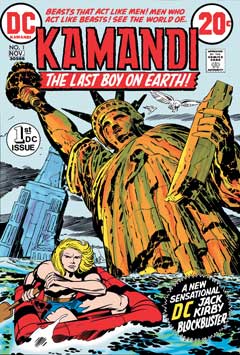

Pope made a pitch to do Kamandi, a character created by comic book legend Jack

Kirby. Touted as “the last boy on Earth,” Kamandi inhabits a post-apocalyptic

world in which animals have risen to become the dominant species. The series

debuted in 1972, at the height of the popularity of the Planet of the Apes

films.

Kamandi ran for 59 issues before it was cancelled in 1978. Since then

the character has made cameo appearances and guest-starred in various titles,

and has been collected into various trade paperback forms.

So Pope made his pitch, the idea being it would be an all-ages

book, only to be stopped midway through.

“We don't publish comics for kids,” the unnamed head of DC is reported to have

said. “We publish comics for 45-year olds. If you want to do comics for kids,

you can do Scooby-Doo.”

Let’s do some math, shall we? The mid-point of Kamandi’s run was #30,

published in early 1975. assuming the average comic reader was 10-years-old at

the time, that would make him now 48.

So basically this unnamed head of DC was saying, “Our target audience is people

who were reading Kamandi back in the mid-’70s as kids.” In my opinion,

he couldn’t be more wrong. I was one of those kids, and there are no DC titles

that interest me.

Based on that statement, it is easy to extrapolate that in 20 years, DC Comics

will be publishing comics for 65-year-olds. It’s a wonderful idea to be able to

maintain a customer throughout their entire life, but what happens when those

customers die off? Where will new readers come from? The answer is obvious: by

appealing to readers of all ages.

Before I continue, I have an beef with the term “all ages,” because

it usually mis-used. It often applies to some G-rated title aimed squarely at

the 10-and-under audience. Consequently, it has no appeal to older comic book

readers, thereby failing to reach all ages.

There was a time when comic book were truly all ages, read and enjoyed

by 10-year-olds, 15-year-olds, 20-year-olds and older. But in the past 20

years or so, comic book companies have begun to throw up walls around their

product, leading to ageism on the part of the publishers. Product aimed at one

segment of comic book readers ignores others.

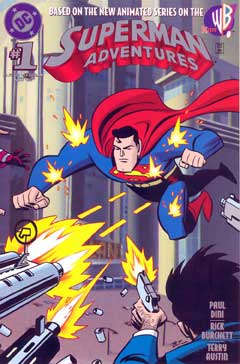

An example of a truly all-ages title would be Superman Adventures, based

on the Superman animated series of the 1990s. The stories were simple, usually

done-in-one, and followed a streamlined continuity yet to be bogged down by the

rest of the DC Universe. Art was simple, perhaps cartoony, but the stories I

remember all had the same level of sophistication I remember from the Superman

titles of the 1970s.

My point is, it can be done. It is possible to reach all ages in a single

title.

I can imagine a time in comics when comic book creators were perhaps handed the

keys to the kingdom. “We like you,” the publisher said. “We think we can do

great things for each other. So take your pick of our properties, come up with

an idea, and maybe we can do business.”

And creators took them up on it, leading to one-shots and limited

series. Characters long dormant – Blackhawk, Sgt. Rock, the Freedom Fighters,

The Secret Six, the Challengers of the Unknown, Animal Man, and so many others

– enjoyed a brief resurrection. Some were more succesful than others, and

perhaps most eventually faded back into the DC Comics archives.

But makes sense to me that when a publisher has a concept languishing in

obscurity, and a talented writer or artist makes a pitch designed to A.) breath

new life into the character; and B.) reach out to new audiences as well as old,

it makes sense not to discourage the creative process.

Artist Brian Stelfreeze collaborated with writer Joe Pruett on a four-issue Domino

series for Marvel in the 2002. To paraphrase his reasoning, the belief was that

Domino was no so high-profile a character that the risk was so great. At best,

the series might push Domino up the strata of bankable properties. If not, and

the series was a failure, well, who was to notice? It was the more popular

characters who have much more to lose in such situations.

Would that more publishers take that same gamble with their lesser known

properties. Marvel facelifted X-Men in the mid-1970s, and parlayed Blade

into a three-film franchise with a TV series to boot. Gambling on a four or

six-issue miniseries seems less expensive than a film or TV production, so why

not let a creator with a proven track record and lot of enthusiasm take a stab

at a property that has stagnated.

It can’t do worse than the New 52 version of Blackhawks.

Praise and adulation? Scorn and ridicule? E-mail me at

philip@comicbookbin.com

Last Updated: November 29, 2025 - 16:51