Trans Identity in Fiction: Life Before Transition

By J. Skyler

January 6, 2013 - 17:03

|

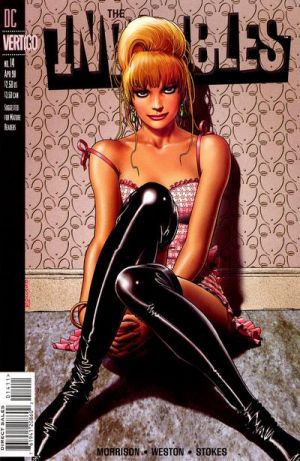

| Cover to The Invisibles #14 (1997) by Grant Morrison and Brian Bolland featuring Lord Fanny, a Male-to-Female (MtF) trans woman, shaman and sex worker |

How do we begin discussing the proper portrayal of trans identities? It is vital to first understand terminology and their implications. While sex and gender were once considered to be synonyms, clinical as well as social-political developments over the past century have revealed they are differing points on the spectrum of the human condition. “Transgender” is an sociological umbrella term which indicates an individual's genetic or anatomical sex is opposite their self-perceived sense of being male or female. The word “transsexual” is slightly more specific in the medical/clinical sense, indicating someone who has yet to complete sex reassignment surgery (SRS), is in the process of transitioning, or who has already completed their transition (designated as per-operative and post-operative, respectively). Transgender/transsexual is opposite of being cisgender/cissexual, words which indicate one's gender identity matches their anatomical sex. To be cisgender is perceived as normative and the natural extension of that mentality is for people to fulfill certain gender role expectations based on their birth sex. It is not at all uncommon for cisgender individuals to have difficulty fulfilling gender role expectations, even though their gender identity is in sync with their anatomical sex. Thus, it goes without saying that for children who become self-aware of their transgender identity at an early age (and who completely disassociate with their physical anatomy), the psychological pressure to conform to the expectations set forth by their families, peers and social imagery and/or commentary in the media can be a terrible burden.

|

Conformity to gender role is indoctrinated essential from birth. I mentioned previously in “I am Not My Penis: A Response to the Roseanne Barr Controversy” that there is a probable neurological causality in psychological gender (for transgender and cisgender people alike), but societal gender roles are largely cultural in context. After all, men doing manual labor and women handling household chores have absolutely nothing to do with biology. Nonetheless, names, toys, color schemes for nurseries and clothing (in addition to clothing itself) and a great deal of social interaction focus exclusively hyper-masculine or hyper-feminine imagery. Even in utero, our lives have a tendency to be mapped out based entirely on our anatomical sex. How many parents have said “I hope he becomes an athlete” or “I hope she takes up ballet” after confirming a pregnancy? The implications of those statements is that little girls do not grow up to become professional athletes and little boys do not grow up to become ballet dancers, even though men and women are quite common in both fields. Granted, there is absolutely nothing wrong with a boy wanting to play sports or a girl wanting to take dance lessons, but such things should be a matter of self-determination, not social obligation. Sadly, parents and peers alike often reward gender-conformity and punish non-conformity, either consciously or subconsciously. We are told habitually what it means to be a “man” and what it means to be a “woman” in life and failing to live up to those expectations can lead to alienation—in familial relationships, friendships and romance—in addition to depression, self-loathing, suicidal or even homicidal tendencies. Trans individuals must endure a great deal to express their perceived gender and it is a daily, life-long struggle.

|

Sadly, most trans men and women are not able to cover the out-of-pocket expenses for any phase of the transitioning process and health care providers quite often will not cover it either. Thus, some members of the community are pre-operative or non-operative, not by choice, but because they lack the financial resources. The lack of trans health care coverage has mostly political implications, as many people mistakenly equate the transitioning process with cosmetic surgery, which can be generally described as procedures which are designed to enhance one's physical appearance to achieve an idealized look. The reality is that transitioning is correctly described as reconstructive surgery—procedures which either restore practical function or establish a standard sense of normality. Reconstructive surgery may apply to (but is not limited to) those who are born with physical abnormalities or who may have suffered disfigurement due to disease or critical injury. Such procedures would not be considered “cosmetic” because they are not designed to indulge vanity, but to establish or reestablish a basic standard of functionality and/or appearance, as is the purpose of transitioning.

Examples set forth above are merely a few of a multitude of issues trans individuals face in our day-to-day lives prior to transition. Unfortunately, such struggles are rarely—if ever—discussed in fiction, or they are conveniently bypassed through the use of science fiction and the supernatural. While transgender and transsexual characters are rare in comic books, literary novels are the primary vehicle through which such themes are explored. Stone Butch Blues by transgender activist Leslie Feinberg is considered to be a landmark piece. Other works, such as Octavia Butler's Dawn (1987), The Left Hand of Darkness (1969) by Ursula K. Le Guin and The Passion of New Eve (1977) by Angela all contain gender-variant themes that range from subtle to overt. Unfortunately, as Robin Anne Reid points out in Women in Science Fiction and Fantasy, Volume 1 (2009), it is much more likely to find trans characters in hentai (pornographic anime) than in mainstream film or any other medium. She goes on to say that “[w]hile some critics equate transsexuality with sexual desire, this claim is frequently refuted within the transsexual community.” The false equivalency of “transsexuality” with “sexual intercourse” is why anything trans-centric can be perceived as “dirty” or unfit for mainstream publication, especially publications directed at teens or children (even though teens and children are a part of said community, as the transitioning process can begin as early as age eight). The knee-jerk reaction to associate trans identity with pornography, in a society where sex is already a taboo (or at the very least dichotomous) subject, makes the task of creating and promoting well-rounded, three-dimensional and self-identified trans characters an absolute nightmare.

So the question becomes "what do we do about it?" The answer is to speak out. The more we publicly discuss our struggles, the harder it becomes for others to ignore them. Are you a casual or avid trans comic book reader? Are you either pre-operative or non-operative? Have you ever had a desire to see something of yourself reflected in the comics you read? If so, what would your request be to major and independent publishers like DC, Marvel, Image, Dark Horse, Valiant, IDW or Zenescope? Send me an e-mail at skyler@comicbookbin.com with the subject “Life Before Transition” or tweet me @jskylerinc with the hashtag #LifeBeforeTransition. I'd like to compile and share responses from trans readers. Let your voices be heard. Also: if you are intersexed and feel you have something to contribute to this discussion, feel free to contact me as well.

Be sure to look for a follow-up: "Trans Identity in Fiction: Life After Transition."

Related Articles:

The Transformers as Transgender?

Bill Willingham's Legenderry #1 Review

How to Write Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Issues: A Guide

Gail Simone to Write Transgender Character

Mystique: Crossing the Boundaries of Sex, Gender and Human Nature